CounterPunch

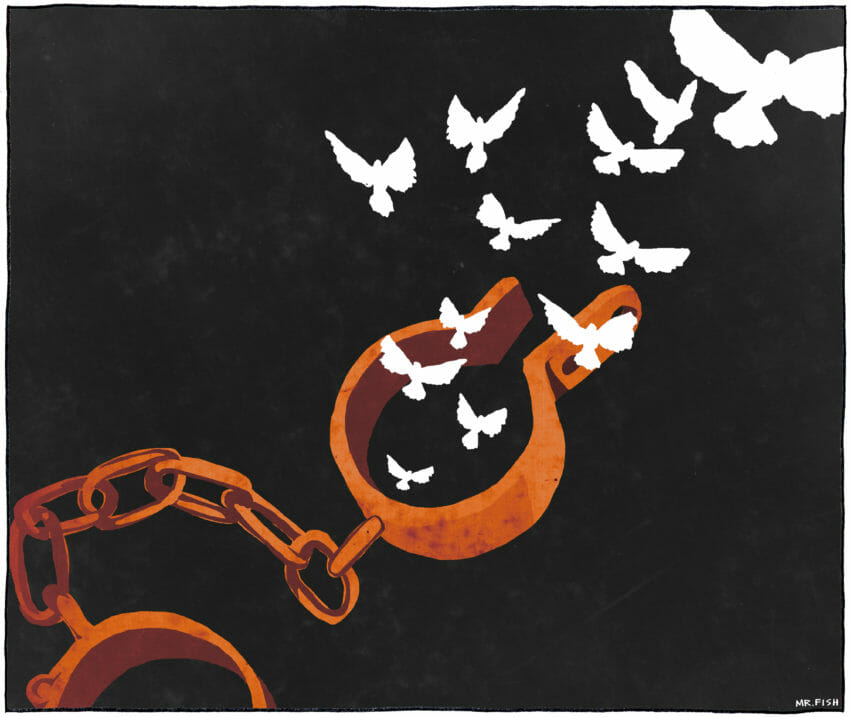

“Doctrine of Futility”

Seventeen years ago, 23 year old Rachel Corrie (a Washington State volunteer with the International Solidarity Movement) was crushed to death by an armored military bulldozer as she stood on top of a mound of dirt trying to prevent the dozer from destroying a civilian home in the Southern Gaza Strip village of Rafa. Wearing a bright orange vest and shouting out at the bulldozer through a megaphone, Corrie was murdered for the temerity of her unarmed act of peaceful defiance. More than a dozen years later the Israeli Supreme Court rejected her parents’ suit to hold Israel’s military accountable for her death. In finding that an “explicit statutory provision of the Knesset overrides the provisions of international law”, the Israeli High Court sacrificed well more than a century of settled international protections, including those memorialized under the laws of war and human rights, to the endless Israeli talisman of “wartime activity.”

More than a few historians can recall that very chant, raised and rejected at the Nuremberg Tribunals, which held Nazis accountable for targeted attacks on civilians throughout World War II.

Less than two months after the murder of Corrie, 34 year old James Henry Dominic Miller (a Welsh cameraman, producer and director who had won five Emmy awards for his work) was shot dead by an Israeli soldier, at night, while filming a documentary in the Rafah refugee camp. Moments after he and his crew left a Palestinian home bearing a white flag, two shots rang out. After the first shot a crew member cried out, “…we are British journalists.”. Soon, a second shot hit Miller, killing him instantly. Initially, one spokesperson reported that after the IDF discovered a tunnel at the house Miller had exited, he was shot in the back when caught in the middle of a crossfire precipitated by an anti-tank missile fired at Israeli troops. Another spokesperson said his death occurred during “…an operation taking place at night, in which the [Israeli] force was under fire and in which the force returned fire with light weapons.”

Later, both versions were retracted when it turned out that the round that killed Miller had entered not through his back but the front of his neck. Likewise, the tale of crossfire fell apart with witnesses reporting no such exchange of gunfire and none having been heard on an audio recording made contemporaneous to the incident.

Some two years later, an Israeli military police investigation into Miller’s killing was closed without returning any criminal charges against the Israeli soldier suspected of firing the fatal shot … though he was to be “disciplined” for violating the rules of engagement and for altering his account of what had occurred.

The following year, an inquest jury at St Pancras Coroner’s Court in London returned a verdict finding that Miller had been “murdered” and that the fatal shot matched rounds used by the IDF. Not long thereafter, the UK Attorney General made a formal request to Israel for it to prosecute the soldier responsible for firing the shot. That request was ignored. To date, no such proceedings have been undertaken by Israel …be it by an independent investigatory body, the military or the office of the state prosecutor.

In March of 2009, thirty-eight year old California native, Tristan Anderson, was hit in the forehead by a high-velocity teargas canister fired directly at him by an Israeli border policeman, some 60 metres away, following a regular joint Palestinian -Jewish demonstration against the Israeli separation barrier in the West Bank village of Ni’lin. When struck, Anderson was simply talking with three or four other activists in the center of the village some distance from the “shame wall” where the demonstration had earlier occurred. In the months prior, four Palestinians had been killed by soldiers during like demonstrations.

Taken to a hospital with his head split open, Anderson underwent three emergency brain operations which required the partial removal of his frontal lobe. The surgery, which left him in a coma and in critical condition, blinded his right eye and paralyzed half of his body. After fifteen months of hospitalization, Anderson returned home where, a decade later, he continues to require around the clock care because of permanent cognitive impairment and physical disability.

Several days after Anderson was crippled, Israeli police opened an investigation into the circumstances of the shooting. Given the 400 plus metre range of the canister, and their respective positions, there was clear evidence of criminal intent on the part of the soldier who shot Anderson. Despite this, the investigation was closed, some six months later, without explanation or any public finding… and with no criminal charges filed against any police or military personnel.

When no criminal charges were filed against those involved, the Andersons filed a civil law suit against Israel but waited years for the case to proceed in an Israeli court. Years later, the case remains very much in a state of judicial limbo with no determination as to it merits. Not unusual at all, counsel for the Anderson’s has noted that “…[t]he astonishing negligence of this investigation and of the prosecutorial team that monitored its outcome is unacceptable, but it epitomizes Israel’s culture of impunity. Tristan’s case is actually not rare; it represents hundreds of other cases of Palestinian victims whose investigations have also failed.”

As she walked out of the courtroom after a judicial proceeding into the civil lawsuit regarding the shooting of her partner, Gabby Silverman, who is Jewish, was served with an order that she had to leave Israel within the following 7 days because there was “insufficient proof that there was a lawsuit going on, and insufficient proof that she is a Jew.”

These three matters involving the murder or cripple of foreign nationals by Israel are very much the rule and not the exception in a state that sees dissent or disobedience as an open invitation for retaliation. For the fortunate, it means but arrest or expulsion for the less so …outright assassination.

For those who survive politically rooted Israeli assault, or their mourning heirs, the road to equity remains a dead end… one blocked by walls of incompetence or indifference… smothered by systemic delay and legislative fiat that convert black robes of justice to mere rubber stamps of state. To be sure, Israel’s failure to promptly and thoroughly investigate facts and circumstances, let alone to prosecute its agents… military or otherwise… who commit crimes against foreign nationals or to provide for an equitable and expeditious civil remedy for them or their loved ones, is well-known, indeed, notorious throughout the world.

For Palestinians, every step outside their home is to navigate a mine field of uncertainty; every encounter with an Israeli soldier or police officer a literal tempt to their life or liberty. The famed Israeli human rights center, B’Tselem, has archived a veritable cemetery of Palestinians victimized by extra-judicial Israeli assassination. Most cry out for justice from beyond the headstones that mark their name with little else but the smile of their memory. Meanwhile, loved ones wait for the call of justice… an echo, for almost all, never to be heard.

On July 13, 2011, twenty-one year old Ibrahim ‘Omar Muhammad Sarhan was shot dead at al-Far’ah Refugee Camp by soldiers who ordered him to stop during an arrest operation. When he refused, he was killed. Though a military investigation into his killing was opened, it was eventually closed, with no one charged, on the grounds “…that the shooting soldier’s conduct was not unreasonable given the overall circumstances and his understanding of the situation at the time.”These horrors are but a microcosm of a deadly, systemic tradition that has raged unabated for generations in which thousands of largely young Palestinians have been targeted, crippled and murdered without penalty of consequence to Israel’s military or security structure… essentially unmonitored and uncontrolled… indifferent to human rights and international law. Yes, there have been those rare empty exceptions in which a perverse judicial performance has made a mockery of life and law with token punishment meted out for crimes that shock the conscience of humanity.

On February 23, 2012 twenty-five year old Tal’at ‘Abd a-Rahman Ziad Ramyeh was shot dead at the northeast corner to a-Ram, al-Quds District, after throwing a firecracker at soldiers during a clash with demonstrators. A military investigation into his death was closed “…on the grounds that the gunfire that killed Ramyeh was carried out in accordance with open fire regulations.”

On March 27, 2012, twenty-seven year old Rashad Dhib Hassan Shawakhah was wounded, in the village of Rammun, when he and his two brothers confronted two out-of-uniform soldiers who approached their home in the middle of the night. Believing the men to be burglars, the brothers, armed with a knife and a club, confronted the soldiers who, without identifying themselves, shot the three of them. Uniformed soldiers arriving at the scene shot Rashad, again, as he lay wounded on the ground. He died six days later. Although a military investigation was opened, more than seven years later no action has yet been taken.

On January 15, 2013, sixteen year old Samir Ahmad Muhammad ‘Awad of Budrus, Ramallah District, was shot and killed by soldiers near the Separation Barrier. After crossing the first barbed wire fence of the barrier, Awad was shot in the back and in the head as he tried to flee the soldiers’ ambush and return to Budrus. Although two soldiers were indicted, several years later, for reckless and negligent use of a firearm, the charges were eventually dismissed when prosecutors told the court that because their evidence had “weakened” there was no longer “…a reasonable prospect of conviction.”

On January 23, 2013, twenty-one year old Lubna Munir Sa’id al-Hanash was shot and killed while walking on the grounds of Al-‘ Arrub College, after a Molotov cocktail was thrown at an Israeli car traveling ahead of the vehicle in which the soldier who fired and the second-in-command of the Yehuda Brigade were passengers. The following year, an investigation into the killing by the military was closed after a finding that the “… shooting did not breach protocol and did not constitute any type of criminal offense.”

On December 7, 2013, fifteen year old Wajih Wajdi Wajih a-Ramahi was shot in the back and killed by soldiers, at the Jalazon Refugee Camp, while standing in the vicinity of teenagers in the camp who were throwing stones at the soldiers from approximately 200 meters away. Six years later, the case remains under military “investigation.”

On March 19, 2014, fourteen year old Yusef Sami Yusef a-Shawamreh of Deir al-‘Asal al-Foqa, Hebron District, was shot by soldiers after he and two friends crossed a gap in the Separation Barrier to gather gundelia [Arabic: ‘Akub], a thistle-like edible plant. Not long thereafter, a military investigation of the shooting was closed with a finding of the “…absence of a suspected breach of open fire regulations or criminal conduct on the part of any military personnel.”

On May 15, 2014, sixteen year old Muhammad Mahmoud ‘Odeh Salameh was shot in the back and killed in a protest near the village of Bitunya, near the Ofer military base, that included stone-throwing. He was not throwing stones when killed. Two years later, the military closed an investigation into the killing after it claimed that no evidence was found connecting a soldier to the shooting.

On July 22, 2014, twenty-nine year old Mahmoud Saleh ‘Ali Hamamreh of Husan, Bethlehem District, was shot in the chest and killed by soldiers when he stepped out of his grocery shop to observe clashes underway in the village. While a military investigation was initiated soon thereafter, four years later no decision has yet to be reached.

On August 10, 2014, ten year old Khalil Muhammad Ahmad al-‘Anati of the al-Fawwar Refugee Camp was shot in the back by a soldier while near other boys who were throwing stones at a military jeep in the Camp. He died of his wounds in hospital. Several years later, a military investigation into the child’s killing ended after “…the investigation found that the troops had acted out of a sense of mortal danger, and that no link between the gunfire and the death of the boy… could be proven.”

On July 23, 2015, fifty-three year old Fallah Hamdi Zamel Abu Maryah of Beit Ummar, Hebron District, was killed after soldiers entered his home, to make an arrest, and shot and wounded his son. When Abu Mariyah threw pottery at the soldiers from a second floor balcony of his home, soldiers shot him three times in the chest. A military “investigation” continues.

On September 18, 2015, twenty-four year old Ahmad ‘Izat ‘Issa Khatatbeh of Beit Furik, Nablus District, who was congenitally deaf, was shot in the back by soldiers near the Beit Furik Checkpoint. He died six days later. To date, it appears no investigation into his killing has been initiated.

On September 22, 2015, eighteen year old Hadil Salah a-Din Sadeq al-Hashlamun of Hebron was shot and killed when hit multiple times in her legs and upper body after refusing to stop on her way out of the Police (Shoter) Checkpoint. As it turned out a concealed knife was recovered from her. No criminal investigation into her killing was undertaken.

On October 5, 2015, thirteen year old ‘Abd a-Rahman Shadi Khalil ‘Obeidallah of the ‘Aydah Refugee Camp, Bethlehem District, was shot dead by soldiers as he stood, with other teenagers, approximately 200 meters away from a military post at Rachel’s Tomb where minor clashes were underway between Palestinians and soldiers. Although a military investigation into the child’s killing was initiated, no decisions have been reached more than four years later.

On November 6, 2015, seventy-two year old Tharwat Ibrahim Suliman a-Sha’rawi was shot dead by soldiers standing on a road after they “suspected” she was trying to run some of them over. Even after the car passed, soldiers continued firing at her. The military reported no investigation was launched as a “…preliminary review of the incident did not indicate suspicion of a criminal offense.”

On November 13, 2015, twenty year old Lafy Yusef Mustafa ‘Awad of Budrus, Ramallah District, was critically injured when shot in the back by soldiers after he broke free from their grasp and began to flee. Driven to hospital in a civilian vehicle, which necessarily took longer because of a military checkpoint, he was pronounced dead upon arrival. No investigation was undertaken as the military stated “…a preliminary review of the incident did not indicate suspicion of a criminal offense.”

On December 11, 2015, fifty-six year old ‘Issa Ibrahim Salameh al-Hrub of Deir Samit, Hebron District was shot and killed by Border Police and soldiers who “suspected” he was trying to run them over. Six months later, the military advised that no investigation would be launched into the incident as a “…preliminary review of the incident did not indicate suspicion of a criminal offense.”

On December 18, 2015, thirty–four year old Nasha’t Jamal ‘Abd a-Razeq ‘Asfur of Sinjil, Ramallah District, was shot and critically wounded, while walking home, by soldiers more than a hundred meters away who opened fire while other Palestinians threw stones at them. He died later that day in hospital. While a military investigation was opened it was apparently closed without any charges.

On February 10, 2016, fifteen years old ‘Omar Yusef Isma’il Madi of the al-‘Arrub Refugee Camp, Hebron District, was shot dead by a soldier in a military tower, at the entrance to the camp, while stones were being thrown at the tower. Though an investigation was launched, more than three year later no conclusion has been reported.

On May 4, 2016, twenty-three year old Arif Sharif ‘Abd al-Ghafar Jaradat of Sa’ir, Hebron District, (who had Down’s syndrome) was shot as he approached soldiers as they were leaving his village. He died six weeks later. Although a military investigation was closed because “…the gunfire at the casualty did not deviate from open-fire regulations” an appeal has been filed.

On June 21, 2016, fifteen year old Mahmoud Raafat Mahmoud Mustafa Badran of Beit ‘Ur a-Tahta, Ramallah, was fatally shot… and four other young men injured… by soldiers who fired on their car while they were driving through a tunnel on their way home from a night at a swimming pool. An investigation was closed by the military which concluded “…in light of the circumstances of the incident, the miss-identification of the car was an honest and reasonable error, and it was permissible for the troops to initiate suspect apprehension procedure.”

On October 20, 2016, fifteen year old Khaled Bahar Ahmad Bahar of Beit Ummar, Hebron District, was shot in the back and killed as he ran into a grove fleeing soldiers. Although an investigation was reportedly begun, more than three year later no action has ensued.

On October 31, 2017, twenty-six year old Muhammad ‘Abdallah ‘Ali Musa of Deir Ballut, was shot dead by soldiers, while driving to Ramallah with his sister, after soldiers had reportedly been alerted that a suspicious vehicle was approaching. Ordering the car to stop, one of the soldiers began to fire at the car, and continued even after it had passed by, without any of its passengers having tried to harm anyone. It was reported that Musa lay wounded on the ground for some 10 minutes without receiving any medical care and was later seized by soldiers while being treated by a Palestinian ambulance team. Two years after the military opened an investigation, it was closed because the soldiers had “…acted in accordance with open-fire regulations and because their operational actions did not evince ethic deficiency.”

On January 30, 2018, sixteen year old Layth Haitham Fathi Abu Na’im of al-Mughayir, Ramallah, was shot in the head and critically injured by a rubber-coated metal bullet fired by a soldier from 20 meters away, after returning to his village post clashes he had taken part in had ended. A military investigation is pending.

On December 4, 2018, twenty-two year old Muhammad Husam ‘Abd a-Latif Hbali of Tulkarm Refugee Camp, was shot in the head by soldiers from behind. Intellectually disabled, when shot, he was moving away from soldiers while carrying a stick. All was quiet at the time he was shot. A military investigation has been on-going since.

On December 14, 2018, eighteen year old Mahmoud Yusef Mahmoud Nakhleh of al-Jalazun Refugee Camp Ramallah, was shot in the back by soldiers from about 80 meters away while running near the entrance to the refugee camp… after others had thrown stones at a military post at its entrance. Soldiers dragged Nakhleh away by the arms and legs and denied him medical treatment for about 15 minutes. He died soon thereafter. A year ago, a military investigation was launched.

On December 20, 2018, seventeen year old Qassem Muhammad ‘Ali ‘Abasi of Ras al-‘Amud, East Jerusalem, was fatally shot in the back by soldiers, who were stationed near a checkpoint, as the car in which he and three of his relatives were passengers was driving away from the checkpoint. A military investigation was opened.

On March 20, 2019, twenty-two year old Ahmad Jamal Mahmoud Manasrah of Wadi Fukin, Bethlehem, was shot dead by a soldier who fired at him from a military tower near a local checkpoint. At the time he was killed, he was helping a family whose car had been shot at by soldiers and had pulled over. An investigation is pending.

On March 7, 2019, seventeen year old Sajed ‘Abd al-Hakim Helmi Muzher, a volunteer medic, from the a-Duheisheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem District, was shot in the stomach as he ran to evacuate a Palestinian who had been shot in the leg when stones were being thrown at troops who had entered the camp. He died later that day. A military investigation is on-going.

Thus, on January 1, 2013, twenty-one year old ‘Udai Muhammad Salameh Darawish of a-Ramadin, Hebron District, was shot dead by soldiers near the Meitar checkpoint as he fled them after he entered Israel, for work purposes, without a permit. Following a military investigation and plea bargain to negligent manslaughter, a soldier received a seven-month suspended sentence and was demoted to sergeant.

Two more recent judicial miscarriages remind us, once again, that law in Israel remains but a gavel for Jews and a bludgeon for all others:

On May 10th of this year, Elor Azaria, an Israeli medic who faced up to 20 years upon his conviction for manslaughter, walked out of prison after serving but nine months of an eighteen month sentence originally imposed on him by a military court. It was subsequently reduced to fourteen months by the IDF chief of staff and then again by the army’s prison parole board (and agreed to by military prosecutors) for his cold-blooded execution of twenty-one year old Abdul Fatah al-Sharif who lay injured and motionless on the ground after stabbing, but not seriously injuring, an Israeli soldier in Occupied Hebron. With calm, deliberate ease, Azaria was recorded as he approached his victim, cocked his rifle and executed him with a single shot to his head.

Not long ago, an Israeli military court sentenced a soldier to one month of the military’s equivalent of community service over the execution of fifteen year old Othman Rami Halles who he shot dead during protests near the Israel fence east of the Gaza Strip on July 13, 2018. The unnamed soldier was convicted for “…acting without authorisation in a manner endangering to life and well-being.”

These sentences pale in comparison to those routinely imposed upon Palestinian children convicted of throwing stones. For example, sixteen year old stone thrower Saleh Ashraf Ishtayya was sentenced to three years and three months in prison. Fourteen year-olds Muhammad Ahmad Jaber and Murad Raed Alqam received three year sentences. Seventeen year old Muhammad Na’el and sixteen year old Zaid Ayed al-Taweel each received two years and four months in prison for the same offense. None of these children injured, let alone, took the life of an Israeli.

Tragically, casualties have long been the anguished, up-close face of the Occupation with an historical character that wields a deadly reach unmatched and long ignored by the world. As very much a perverse rite of passage, thousands of Palestinian civilians have paid the ultimate price for little more than their presence… lost to multiple high-tech military operations that have targeted residential communities and schools, hospitals and core infrastructure. Many more have been wounded or crippled by relentless Israeli attacks designed to leave survivors not just overwhelmed and battered but with a sense of isolation and futility. Nowhere has this brutal assault on fundamental human rights and international law been more conspicuous than through the sniper attacks on Gaza, over the past 18 months, that have slaughtered or injured tens of thousands of demonstrators whose only weapons have been the step of their march and the resound of their voice. And what of international law?

Volumes have been written on humanitarian law… the law of war and human rights. No doubt they line the walls of judicial halls throughout Israel… from its lowest military courtroom in the Occupied Territories to the highest civilian chamber that claims to rule supreme as the guardian of due process and equal protection for Israeli citizens and those held captive by it. Yet, even a cursory glance by an untrained eye leaves the imprint of a judicial system that is subservient to the chant of state security and legislative fiat and slowed to a process of delay that drags on and on for years leaving no one but Israeli Jews comfortable in the notion that they will have their day in court and with speed and fairness.

Millions of Palestinians are held captive in the Occupied Territories be it in the West Bank by security onslaught or military patrol or by the heap of Concertina wire, sniper mounds and air force and naval watch that keeps all of Gaza imprisoned every minute of every hour of every day. For these foreign nationals… and they are foreign nationals… they never see the inside of an Israeli civilian court or the due process it infers. For these perpetual prisoners, the uniformed soldiers that carry weapons become uniformed soldiers that investigate and prosecute cases to uniformed soldiers that pass judgment adorned not by robes of independence but by order of salute. As noted above in the archive of causality, few if any Palestinians ever obtain due process and equal protection of the law, let alone with independent and foreseeable resolution, as investigations and cases linger on for years pushed, predictably, to the back of the line as each new public outrage unfolds. This is not justice but the “Doctrine of Futility” at its primordial worst.

International Relief

It is settled law that before seeking international relief, aggrieved parties must first seek redress for harm, caused by a state, within its own domestic legal system. Exhaustion of local remedies (ELR) is intended to uphold state sovereignty by recognizing its own judicial process as a presumptive vehicle for the independent, equitable and expeditious resolution of claims against the state. ELR presumes a state’s judicial and administrative systems provide for a credible and apolitical avenue for injured foreign nationals to obtain their day in court before moving-on for diplomatic protection or undertaking international proceedings directly against the state. Yet, very much the proverbial beauty locked in the eyes of the beholder, provisions like equitable, independent and expeditious are routinely recast by repressive regimes across the globe to mirror little more than partisan safeguard of the state’s tyrannical needs and agenda.

Nowhere is that more palpably evident or painfully clear than it is in Israel where judicial remedies have long and repeatedly proven to be little more than a convenient faith based tease… a non-existent march to the beat of the overarching political gavel of the Knesset. For Israeli Jews, “all rise” portends opportunity denied all others. For Israeli Jews, lady justice cheats as she peeks out from behind her blindfold… for all others, she is but a symbol without a sign.

The ELR rule is a foundational mainstay of all global and regional international human rights entities and covenants. For example, within the UN, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights mandates that it’s Human Rights Committee “shall deal with a matter referred to it only after it has ascertained that all available domestic remedies have been invoked and exhausted in the matter, in conformity with the generally recognized principles of international law.”

Likewise, the European Convention on Human Rights provides that the European Court of Human Rights “may only deal with the matter after all domestic remedies have been exhausted, according to the generally recognized rules of international law.”

The American Convention on Human Rights requires exhaustion of local remedies “in accordance with generally recognized principles of international law” before the submission of petitions or communications to the commission.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights provides that the Commission “can only deal with a matter submitted to it after making sure that all local remedies, if they exist, have been exhausted, unless it is obvious to the Commission that the procedure of achieving these remedies would be unduly prolonged.”

This exemption is but one of several that find smooth fit within the so-called “Doctrine of Futility.” Under this doctrine, while release from the requirements of the ELR fluctuates from venue to venue, by-in-large one need not chase domestic justice where none can be had. Thus, in general, ELR may be bypassed:

a. If the domestic legislation of the state concerned does not afford due process of law for the protection of the right or rights that have allegedly been violated;Israel is a veritable primer, a law school’s teach, on when and where all three damning exemptions merge to validate an apt and speedy march to the nearest international forum in pursuit of justice and human rights otherwise willfully denied foreign nationals in any courthouse or military barrack that flies the banner of the Star of David.

b. If the party alleging violation of his rights has been denied access to the remedies under domestic law or has been prevented from exhausting them; or

c. If there has been unwarranted delay in rendering a final judgment under these remedies.

And just who are foreign nationals? In most jurisdictions they cut a relatively narrow swath; typically but a handful of tourists, temporary workers, or businesses and those incidentally injured by practices of cross-border states. Yet, the numbers balloon to millions of foreign nationals in occupied Palestine where all aspects of every Palestinian’s life is impacted… if not controlled… daily by an occupation force and judicial process of another state.

Independent of the pervasive culture of military and security violence and its companion lack of fairness and accountability, the Israeli judicial system… both criminal and civil… presents a compelling case study in a double standard delayed and disabled based solely upon ones faith and national identity.

Child Prisoners

Over the last two decades, more than 8,000 Palestinian children (foreign nationals) have been arrested in the Occupied Territories and prosecuted in an Israeli military system devoid of any meaningful due process or equal protection for the most vulnerable and traumatized among those that have known nothing but the bark of occupation their entire lives. It is a military justice process notorious for the systematic ill-treatment and torture of Palestinian children.

Several hours after their arrest, these children arrive at an interrogation and detention center alone, tired, and frightened. All interrogations, by their very nature, are inherently coercive no matter the age or experience of its victim. None are more so than for an often bruised and scared child forced to go through the process without the benefit of counsel or the presence of parents who are never permitted to participate.

Israeli law provides that all military interrogations must be undertaken in a prisoner’s native language and that any statement made must be reduced to writing in that language. Despite this prohibition, Palestinian detainees are typically coerced into signing statements, through verbal abuse, threats, and physical violence, that is memorialized by police in Hebrew… which most cannot understand. These statements usually provide the main evidence against children in Israeli military courts.

The Military Court Process

The military “courts” themselves are held inside military bases and closed to the public… and usually family members of the accused. Within these courts, military orders supersede Israeli civilian and international law.

In military courts, all parties… the judge, prosecutor and translators… are members of the Israeli armed forces. The judges are military officers with minimal judicial training and, by-in- large, served as military prosecutors before assuming the bench. The prosecutors are Israeli soldiers, some not yet certified as attorneys by the Israeli Bar. Under the rules of Occupation, all defendants in military courts are Palestinian… as the jurisdiction of the Israeli military court never extends to some eight hundred thousand Jewish settlers living in the West Bank who are accorded the full panoply and safeguard of Israeli civil law.

Under military law, Palestinians can be held without charge, for the purpose of interrogation, for a total period of 90 days during which they are denied the benefit of counsel. Detention can be extended without limit and requires but an ex parte request of military prosecutors. By comparison, a Jewish citizen accused of a security offense, within the Occupied Territory, can be held without indictment in the civil process for a period of up to 64 days during which time counsel is available at all times.

Though Palestinian detainees are entitled to military trials which must be completed within eighteen months of their arrest, their detention can be extended indefinitely, by a military judge, in multiple six-month increments. It is this limitless process which has left thousands of Palestinian political detainees imprisoned for years on end without the benefit of counsel, formal charges, or trial. The comparable time limit for detainees in Israeli civilian courts is no more than nine months.

While criminal liability begins at age twelve for Palestinians and Israelis alike, under the military system Palestinians can be tried as adults at sixteen. For Israelis, prosecution as an adult in a civilian court is eighteen. This two year difference, without physical distinction of consequence, can mean a sentence disparity of many years should a conviction ensue. In some cases, it can literally mean a difference between a few years in prison versus decades upon conviction.

Although the United Nations has repeatedly held that the military justice system in the Occupied Territory violates international law, it has done nothing to ensure equal protection and due process to hundreds of thousands denied justice by virtue of being Palestinian and nothing else. This continues to be true for Palestinian minors. According to B’tselem “…at the end of October 2019, 185 Palestinian minors were held in Israeli prisons as security detainees and prisoners, including one under the age of 14.”

Neighborhood Cleansing

With the onset of the Occupation in 1967, Israel initiated a wide range of largely extrajudicial strategies in its incessant effort to claim new municipal boundaries and to remake the age old Palestinian character of east Jerusalem. What began with the seize of large swaths of vacant land surrounding the Old City… for the construction of illegal Jewish settlements… eventually gave rise to the de facto annexation of East Jerusalem… universally condemned as a flaunt of international law. However, never ones to allow legal standards to become barricade to political needs, successive Israeli governments have accelerated the Judaization of the historic capital of Palestine, typically using the call of security as a pretext, while Israel’s judiciary has looked away…largely indifferent to its responsibility to ensure that equal justice be done.

Recently, Israel destroyed 10 mostly unfinished buildings containing some 70 apartments, in the Wadi Hummus neighborhood on the edge of southeast Jerusalem, which were being built with permits issued by the Palestinian Authority in an area under its recognized jurisdiction. Displacing 17 Palestinians, including an older couple and five children, from apartments that were finished, the demolitions also left several hundred others, awaiting housing in the buildings, saddled with ensuing economic loss. Though condemned by the United Nations, the government nonetheless proceeded with the demolitions after Israel’s High Court refused to intervene on the grounds that the project was being built in a military-declared buffer zone near a “security” fence that had gone up years before. That barrier, which is part of the system of steel fences and concrete walls which runs throughout the West Bank and around Jerusalem, was subsequently found to be illegal by the International Court of Justice in 2004. Like hundreds of other international declarations, Israel ignored the findings.

The destruction of these residential buildings is by no means an isolated or unpredictable phenomenon. In point of fact, another one-hundred buildings completed, or under construction, under similar circumstances in the same neighborhood, face the same risk.

While the proffered basis for demolitions has changed to suit the Israeli needs of the moment, they play an essential mainstay in its intended policy of ethnic cleansing throughout east Jerusalem. This modern-day pogrom finds its genesis in a cap that was placed on the expansion of Palestinian neighborhoods in the days following the seizure of east Jerusalem, thereby forcing many to build illegally according to the laws of the Occupation. This artificial limit has been exacerbated by systemic discrimination when it comes to the issue of building permits in east Jerusalem. Though Palestinians make up more than 60% of the population of the Old City according to the Israeli civil rights group Peace Now, they have received just 30% of the building permits issued by Israel dating back to 1991. Given these circumstances, it has been estimated that more than twenty-thousand housing units built in traditional Palestinian neighborhoods dating back to 1967 fall into the category of illegal… thus placing them at risk of demolition no matter what their condition, how long they have stood or the numbers of their occupants.

This danger has found new impetus since the United States moved its Embassy to east Jerusalem, essentially declaring it to be the capital of Israel. Emboldened by this act, and not now fearing either political or economic reprisal by the United States (or meaningful intervention by its own courts), Israel has recently accelerated its demolition policy leading to the destruction of several hundred residential and commercial structures… leaving hundreds of Palestinians homeless and dozens of businesses in ruins.

While precise figures are unknown, it is estimated that, over the last fifteen years, more than one thousand- five hundred residential and commercial units have been demolished by Israel leaving more than three-thousand Palestinians homeless… including some one thousand- five hundred minors.

Of late, we have seen an increase in the number of demolitions carried out by Palestinians, themselves. While some construe the demolition of several dozen Palestinian structures by their own residents as almost a willful, romanticized act of political defiance, self-demolition has less to do with self-determination than it does the unbearable cruelty and cost of the moment. The aching reality is that a judicial system without justice has authorized the state to bill those for the cost of the destruction of their own homes… lest they do so themselves.

Collective Punishment

While Israeli authorities have argued that punitive home demolitions provide “…a severe message of deterrence to terrorists and their accomplices”, such demolitions violate the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as a host of Israel’s human rights obligations… in particular that no-one should be punished for an act they did not commit. Under Israeli law, those subject to punitive home demolitions are accorded an opportunity to appeal a demolition order to a court. However, Israel’s High Court has routinely refused to consider the absolute prohibition in customary international law against collective punishment of civilians in occupied territory when ruling on petitions against punitive home demolitions in the West Bank, including in east Jerusalem. As almost settled law, the Court has held that demolitions can, in general, be justified as “proportionate” when balanced against the need to deter other Palestinians from carrying out future attacks. Moreover, as a practical matter, rare are the opportunities for prospective victims to obtain timely judicial relief thru applications for review of looming military demolitions.

Thus, according to Article 119 of the Military Authority, the IDF commanders responsible for application of military measures in the West Bank and East Jerusalem are empowered to confiscate and demolish any property, if he determines that the inhabitant…and not necessarily owner… of the property resorted to terrorist violence. That power is not vested or required to go through judicial process but rather is purely administrative. Thus there is no need for a court order to authorize house demolitions and the evidence required to demolish a home carries for the military a low threshold of internal administrative proof …“…convincing in the eyes of a reasonable decision maker.”

Though reprisal has long enjoyed a high degree of support among the Israeli public, and thus politicians, there can be no reasoned debate over whether house demolitions constitute a form of collective punishment, and thus a war crime. Prohibited under basic principles of human rights law and Articles 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 and Article 50 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, demolitions also constitute cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment and are selectively applied as against Palestinians and never Jews who commit acts of terrorism.

At their core, these demolitions, which also violate the prohibition on the destruction of private property set forth under Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and Article 23(g) of the 1907 Hague Regulations, seek not to penalize a “terrorist” who is likely dead or in custody charged with serious offenses and facing years, if not decades, in prison, but rather, family members who reside in the home targeted for military reprisal. Thus, innocent parents, husbands or wives, children and siblings or other residents are left homeless as they are forced to bear the consequences of the acts of loved ones, even in the absence of any prior knowledge or nexus to them.

Although Israel has periodically suspended home demolitions, in times of heightened tension or militant resistance they have become very much part of the military mainstream since the onset of the Occupation. While the exact number of such demolitions is neither documented nor certain, it is estimated that more than 2,000 Palestinian homes have been destroyed pursuant to Article 119 since 1967. Though the Israeli High Court requires the IDF commander to hold a hearing for the residents of a property to be destroyed and permits a petition to the court to stay the demolition, these “safeguards” have proven to be a promise without purpose. While the court has stressed those demolitions are harsh security measures that should be used only in “extreme circumstances” not once has it overridden the authority of the IDF to proceed accordingly.

Lest there be any doubt that history can be but a harbinger of things to come, some of those that run the bulldozer of today in Palestine are progeny of those who picked through the rubble of homes and businesses ransacked and destroyed as collective punishment for acts of terrorism. Undoubtedly a pretext, in 1938, following the assassination of a German Embassy attaché in Paris by a young Polish-German Jew, a campaign of collective reprisal was unleashed against Jews in Germany. Known as Kristallnacht, crowds set fire to synagogues, smashed shop windows, demolished furniture and stocks of goods with the approval of the German Government. Years later Nazis applied the principle of Sippenhaft (collective responsibility) to avenge the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich ,the architect of the “Final Solution to the Jewish question”, through mass executions and the destruction of two Czech villages… Lidice and Lezaky.

With predictable promote, Prime Minister Netanyahu recently indicted the ICC investigation of Israel for war crimes and crimes against humanity as little more than anti-Semitism. Putting aside Netanyahu’s readily transparent canard, at its core, the ICC typically does not exercise its jurisdiction pursuant to the Rome Statute unless and until a state fails to provide a meaningful domestic remedy for violations of international law. On this score, few can deny that no such equitable and effective opportunity exists within Israel. As noted by Human Rights Watch, “…the impetus for the establishment of the ICC is the stark failure of national court systems to hold the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes accountable under law.”

Be it by virtue of the blanket political control of the Knesset or the deadly untamed reach of its security apparatus, Israel’s judiciary stands as an emasculated reminder that foreign nationals, whether occupied Palestinians or Westerners seen as enemies of the state, have not, and cannot, obtain due process and equal protection of the law, let alone in an independent and expeditious manner, through Israel’s judicial process. Under these circumstances, the Doctrine of Futility overshadows the need to exhaust local remedies to seek international relief for domestic wrongs. The Doctrine does not provide for an easy and settled pathway for foreign nationals to obtain justice outside the confines of extant domestic procedure. Yet, at its core, this international exemption finds its greatest potential and need when and where, as here, a judicial system is built upon a double standard of law… one for Palestinians, the other for Jews.

Stanley L. Cohen is lawyer and activist in New York City.